2021 Southern Challenge Sites

By Craig O. Olsen

Originally Published in the IAMC Newsletter, August 2012

July 18, 2012: Wells, I am off to my usual late start of visiting the 2012 IAMC Challenge Sites. On a bike trip to St. George, Utah, for my niece’s wedding, I visited my first one.

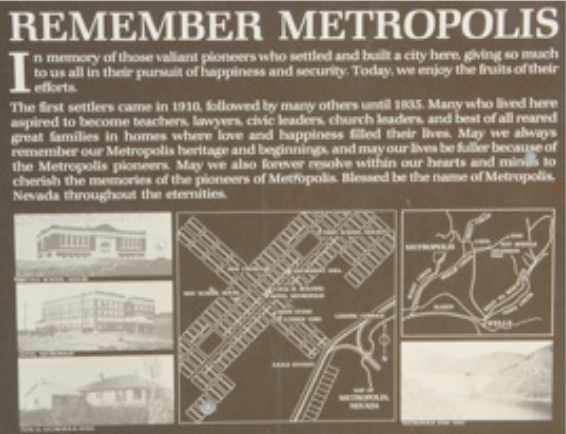

About 10 miles northwest of Wells, Nevada, as the crow flies, is the historical ghost town of Metropolis (Site #-22). Harry L Pierce, an eastern businessman or Leominster, Massachusetts, created Metropolis, a planned town site intended to be the center of a huge farming district. With the backing of Pierce’s Pacific Reclamation Company and investors from Massachusetts and Salt Lake City, 40,000 acres of desert land were purchased in 1910, and P.J. Morgan, a respected Salt Lake City contractor, was hired to build a hundred food high dam on Bishop Creek about 8 miles east of the planned city. The build of the dam comprised 6.5 million broken bricks left over from the San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

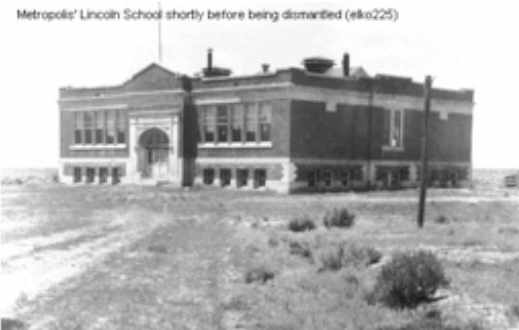

Irrigation canals for the farms and a water distribution system for the town were built. The Southern Pacific Railroad constructed an eight-mile spur from its mail like to a newly constructed, elaborate depot. In addition to the depot, the Pacific Reclamation Company built an amusement hall that features a stage and served as the town’s social center, a post office, a school, and a three story, fifty-room elaborate brick hotel complete with an electric generator, central heating and hot and cold running water in every room. The hotel cost $100,000 to construct and was extremely ornate. It had Douglas Fir paneling and a floor made of imported title. The hotel’s fist floor housed a bank, barbershop, drugstore and a general store. A gala grand opening took place on December 29, 1911, and dignitaries from all over the west visited Metropolis. The town plot and street were laid out for an anticipated population of 7,500.

By the end of 1911 the population had grown to 700. Dry farm land sold at $10 to $15 an acre while irrigated farmland sold at $75 per acre. Town lots sold between $100 and $300.

Unfortunately Pierce had failed to obtain water rights to Bishop Creek, and the community of Lovelace located some 200 miles down stream on the Humboldt River, side the Pacific Reclamation Company from using certain creeks in the headwaters of the Humboldt River, thus preventing the impoundment of water behind Bishop Creek Dam, and the reservoir behind it was never filled completely with water. The court only allowed enough water to the farmers of Metropolis to irritate 4,000 acres. The Pacific Reclamation Company was forced into receivership by 1913 and declared bankrupt in 1920.

Without sufficient irrigation water, dry farming was tried and was successful at first due to unusually high precipitation that lasted only a few years. 1914 was an exceptionally dry year and the drought continued through 1918. In addition, the settlers killed off marauding coyotes that allowed the jackrabbit population to rise dramatically, and the rabbits systematically ate the wheat. The farmers responded with guns, poison and organized drives, killing thousands of jackrabbits. Infestations of crickets as devoted their crops.

If that wasn’t enough, a typhoid epidemic in February 1916 killed many of those who stayed.

In 1922 the railroad discontinued service to Metropolis, and by 1924 only 200 people remained. The famed hotel burned down in 1936, the post office closed in 1942, and the school closed in 1947 when the last residents moved out of Metropolis. Many buildings were moved to other locations. The ruins of the hotel and school and a cemetery are all the remain today. [1-5]

Tuscarora (Site #-28) is located about 41 miles northwest of Elko and 39 miles southwest of Mountain City, Nevada. While Metropolis is large part perished from lack of water, Tuscarora had an abundance of water that few Nevada mining towns had. This site traces its origins to July 1867 when a prospecting party that set out from Austin in central Nevada found gold placer deposits along McCann Creek. Charles Benson, member of that party, suggested naming the new mining district Tuscarora after the United States gunboat of the same name on which he had served during the Civil War. This guested was unanimously approved.

Also among the initial prospecting party, the Bard brothers build an adobe fort from protection against feared Indian attached that need materialized. A small camp of prospectors formed around the Beard’s fort forming the nucleus of Tuscarora.

Following completion of the transcontinental railroad, many Chinese workers were attracted to the placer mining during g1869, and they formed a Chinatown adjacent to the camp of Tuscarora. The Chinese were much more efficient at placer mining that their White contemporaries. By 1870 Tuscarora had a population of 119 of which 104 were Chinese and 15 were White.

The frustrated White miners branched out from the placer sites and began prospecting the surrounding hills. In 1871, W. O. Weed discovered silver ore on the slopes of Mount Blitzen, located about two miles north of the original camp. The new and present townsite of Tuscarora was relocated nearby, and by July of that year a post office was established. It closed briefly in October 1872 and was then reopened again in April 1873.

The initial growth of Tuscarora was slowed b the discovery of tiger ore deposits at Cornucopia located about 16 miles to the north that drained off many of the miners. With the discovery of rich silver vein on Mount Blitzen that became the Grand Deposit Mine in August 1875, miners began flocking to the new Tuscarora town site, and by the summer of 1877 the population had reached 3,000 rivaling Elko as the biggest town in the county.

New businesses, many saloons, a hotel, lodging houses, several stage lines and two news papers sprang up. A jail was built in 1877 though it was not used much. Any serious criminals where always taken to Elko. By 1880 Tuscarora was well stabled with a Schoo of 140 students and two teachers. In January of that year the Tuscarora Polytechnic Institute opened under the leadership of Professor J. F. Burner. The Tuscarora Jockey Club was organized with admission to the racetrack, located just below town, set at 15 cents. Two brewing companies were build and additional mines were opened in the area.

By the mid 1880s the big mines began to play out and close. Tuscarora’s population slipped to less that 1,000 by 1883. Many of the businesses closed, and only the Elko to Tuscarora stage line was left. Tuscarora’s population was 669 in 1900 with many leaving during the next few years. The final wooden coach of the Tuscarora to Elko stage line was retired in August 1913.

Since the 1920’s the town’s population was remained below 50. Today, Tuscarora is classified as a ghost town even though there are still about 20 people living there. Some of the old buildings are occupied. There are other empty building amid newer ones and trailers. The post office is still in operation.

In its heyday from 1870 to 1880 Tuscarora’s mines produced at $40,000,000 in silver. [6-8]

Charleston (Site # -24) is next on the list. Charleston is located about 15 miles south-southwest of Jarbidge, Nevada. I twas originally named Marids after George Washington Mardis who discovers placer gold on 76 Creek in 1867,

Mardis’ appearance was intimidating, having suffered an accidental mining explosion at Mountain City that took one of his eye and scarred and blackened one side of is face. Following the accident, he became a bible-quoting preacher. Once while drunk he got in a fight rendering his opponent unconscious. The crowd convinced him that he had killed the other man, and panicking, he disappeared for a couple weeks. When he learned of the ruse, he never drank again. He had a reputation for honesty, and other mines trusted him to carry their gold to the banks in Elko as he hauled ore from many northern Elko County mines to Deeth.

There were already several other mines in the district that had been active since the early 1870’s. The town of Mardis grew quickly and soon contained a number of stores, a hotel, an icehouse and a school. It also had a widespread reputation for lawlessness.

In September 1880 George Washington Mardis was robbed and killed by a Chinese miner while making a trip to Elko carrying miner’s gold to deposit as well as $250 to buy supplies for Gold Creek’s Chinatown. The town of Mardis faded quickly after his death, and by 1883 only a handful of people remained there. By 1890 the population had grown to 41, and it was renamed Charleston after Ton Charles, a local miner. Again, a number of businesses sprang up in the town. In 1897 a stage line from Deeth, Nevada stated up. The fare to Charleston was $3.50.

In 1900 a school opened when the large Pinkard Prunty family with 12 children came to town. Prunty family descendants still occupy the region today. The economy in the region has switched from mining to cattle ranching. Today, the town of Charleston has completely disappeared. Some of the buildings were moved to nearby ranches while others have succumbed to the elements. The once bustling town site is marked only by a couple of foundations, now behind a locked gate on private property approximately a quarter mile south of the current designated town site. There is considerable evidence of past mining activities in the area, especially north of Charleston along 76 Creek. [9-10]

Jarbidge (Site #-23) is nestled high (elevation 6,200 feet) in a narrow canyon along the Jarbidge River between the Copper and Jarbidge Mountain ranges about 8 miles south of the Idaho-Nevada border. An unincorporated community in Elko County, Nevada, Jarbidge gets its name from the Shoshone world “Jahabich” which means “devil” – the Shoshone name for the nearby mountains. For the Shoshone, the canyon was the forbidden home of Tasu-hau-bitts, a man-eating giant that roamed the mountains snatching up helpless Shoshones and returning to the canyon to eat them.

Prospectors unsuccessfully explored the canyon in the 1860s another prospecting party gave rise to one of Jarbidge’s most enduring legends, the legend of the lost gold mine. The story was born when a man Hamed Ross found a rich gold-bearing gloat somewhere in the heart of the Jarbidge Mountains, but was forced to leave the mountains by a snowstorm. On his way out, Ross met a local sheepherded named Russ Ishman and told him about the discovery. Ross’s plan was to return the next spring and stake his claim. When Ishman returned to the Jarbidge mountains the following year with his herd of sheep, he diced to search for the location described by Ross. Legend has it that Ishman found it. He also found something else. Next to the fish gold-bearing float was a human skeleton. Undeterred, Ishman traced the float uphill to a ledge of quartz literally “shot through with gold.” He gathered a few of the richest samples and eventually returned to the ranch with his sheep herd. Here he showed the gold samples to his boss, Jon Pence. Unfortunately, Ishman was never able to return to the gold ledge. He died soon after his discovery from a cerebral hemorrhage. John Pence had actually seen and held Ishman’s samples and therefore knew that a rich gold deposit existed somewhere in the Jarbidge Mountains. He searched for the ledge many times but never found it.

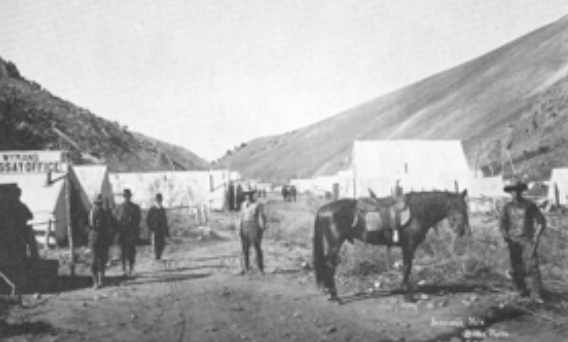

A gold strike on August 19, 1909, prompted a rush of some 1,500 miners into the deep canyon to stake claims on snow drifts as deep as 18 feet. When the snow melted, it exposed the exaggeration of the newspaper reports, and most of the claims melted away with the snow. Further discoveries were made in 1910, and by the end of that year, Jarbidge was a long narrow community of several hundred residents connected by stagecoach with its nearest neighbor, Rogerson, Idaho, some 65 miles away to the northeast. Its population swelled to about 2,000 by 1911.

The last stagecoach robbery in the West took place at the outskirts of Jarbidge during the December blizzard in 1916. The robber killed the stagecoach driver and made off with $3,000 cash and the mail. After capture, the robber was convicted of his crime on the basis of blood finger and palm prints he left on mail envelopes he carelessly threw away. This was the first time such evidence was admissible in court.

In 1918 the Elmore Minding Company build a large mill in Jarbidge and brought electricity to town. This company dominated mining and employment in Jarbidge until the Depression. As it turned out, Jarbidge was the last big boomtown in Nevada mining history. It lasted until 1932 bringing in an estimated $10,000,000 in gold and silver.

Today, the population of Jarbidge is somewhere between 20 and 50 people, increasing during the summer and early fall and decreasing during the harsh winter months. Many old buildings are still standing, some currently being used, and there are news structures as well. [11-14]

About 14 miles west-northwest of Jarbidge is the ranching community of Rowland, Nevada (Site #-21). While there were a number of smaller ranches were homesteaded in the Rowland area during the 1980s, the small ranching community did not form until the 1890s. Initially it was named Bueasta, a conglomeration of the names of three local ranchers – Frank Buschaizza, Lou Eastman, and Joe Taylor.

The Mountain Home to Gold Creek stage ran through Joe Taylor’s Ranch, thus servicing the area. Taylor was the first settler in the area, and the first post office in the area was opened at his homestead in November 1869. This post office closed in February 1898. John Scott bought the Taylor ranch shortly thereafter, and a new rancher, Rowland Gill, settled in the area. When the new post office opened in March 1900 at the Scott home, its as called Rowland in Gills honor. Scott added a store that supplied groceries, clothing and farm supplies for the area. An assay office, saloon and school were also added. A sawmill was also active during this time. By 19920 John Scott owned most of the Rowland area.

Mining started to have an impact on Rowland in 1924, and by September 1925 construction on a stamp mill was started along with a bunkhouse for mill workers, cookhouse, power plant, dam and a flume system. The mines and mill did not produce significant profit, and by August 1927 they closed.

Scott died in February 1930 and soon after his wife sold his holdings. The Scott store closed, and the development at the mine and mill because the new town of Rowland. The post office and school also moved to this location situated about a mile south of the original town. The mine and mill were reopened by only operated intermittently until 1939 when they were closed for good and all mining operations in the area ceased.

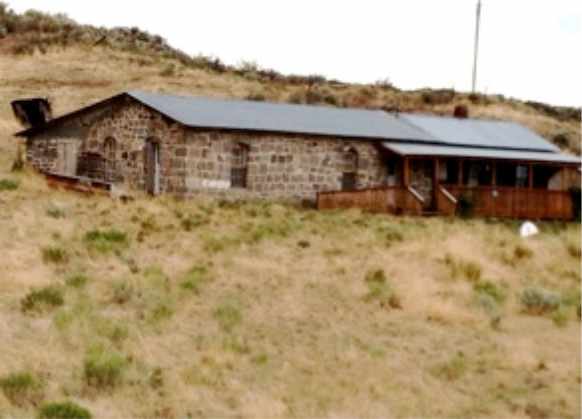

Chauncey Olson built a new store near the mill in August 1930. It survived a fire in 1936, but finally closed in 1942. The post office also closed in November of that year. Over the many years many of the small ranches that made up the Rowland area have been sold and consolidated to make larger ones. A few of the original buildings of the old Rowland remain in tact on the sold Scott Ranch including the stone store, now used as a storage shed. Only the remains located at the new Rowland are the ruins of the mill. [15-17]

Last on the list if Three Creek (Site #-17) located about 20 miles northwest of Jarbidge, Nevada, and 31 miles west of Roberson, Idaho. Three Creek is a ranching area in southeast Owyhee County. Joe Scott of Miles City, Montana, established the first ranch in the areas in the 1870s. The Sparks, Harrell Co. of Visalia, California was the principle ranch in the Three Creek Area in 1898.

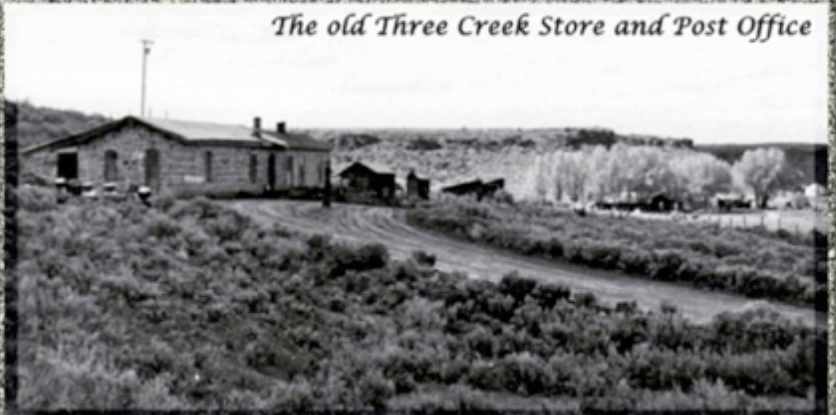

Prior to 1910, for census purposes the Three Creek area was known as the Big Fat Percent, and the 1890 census showed a population of 63. That increased to high of 191 in 1910, but by 1950 the population was back down to 63. The town of Three Creek consisted of a general store built from rocks quarried from nearby creeks, a hotel, a post office and a school. The stone stores is the only building still standing, and it is located on the Three Creek road that runs fromRogerson to Murphy Host Springs about 7 miles west of the GPS coordinates listed on the IAMC Challenge Forum for this site (obtained from iTouchMap.com). The correct coordinates are: N42.07113 W115.16042

IT is not clear when the storm general store was built, but it was owned by Jim and Lizzie Duncan in 1900. An interesting legend this store and its owner is told that sometime around mid September 1900, Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid and Will Carver traveled from their hideout at Powder Springs on the Wyoming-Colorado border, passing through Three Creek on their way to rob the First National Bank in Winnemucca, Nevada which took place on September 19, 1900.

According to Sundance, the robbers got Jim out of bed, and at gunpoint, had hi fill their order for grub, which Jim then loaded on two packhorses. The grub and horses were then cached somewhere only the 200 plus miles to Winnemucca and used in the robber’s escaped after the bank robbery.

Burch Cassidy had promised to pay Jim Duncan for the grub, and as the robbers passed back through Three Creek late one night on their return trip, they figured up the bill for the group, and doubling it, they left it in a sack by the store.

What is the problem with this legend. There is no proof that Burch Cassidy or the Sundance Kid participated in the September 19, 1900 robbery of the First National Bank in Winnemucca. Quite to the contrary, there is compelling evidence that they were not involved at all, which begs the question of who robbed the Three Creek store if it was robbed at all. Anyway, it makes good adventure.

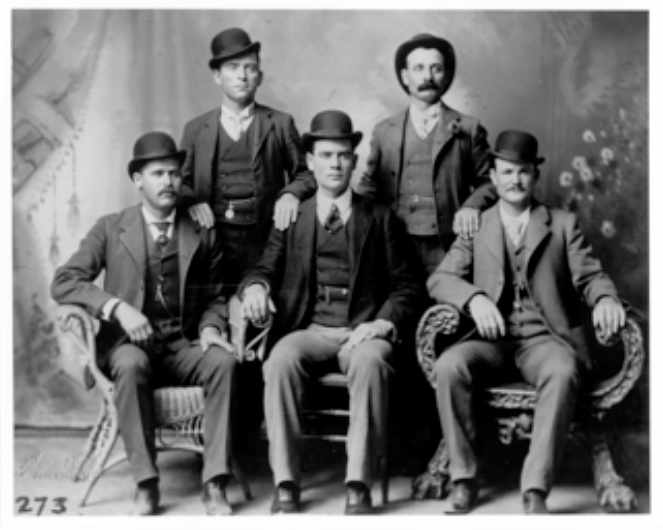

Left to Right: Standing, Bill Carver and Harvey Logan (“Kid Curry”)

Seated, Harry Longbough (“the Sundance Kid”), Ben Kilpatrick(“the Tall Texan”), Robert Leroy Parker (“Butch Cassidy”)

References:

1. Nevada ghost towns ‐ Metropolis. http://www.ghoscowns.com/states/nv/metropolis.html

2. Metropolis. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolis,_Nevada

3. Superman Super Site ‐ Metropolis. http://www.supermansupersite.com/metropolisnev.html

4. Metropolis. http://www.oldiesmusicradio.com/met.htm

5. History of Metropolis Nevada. http://www.elkorose.com/metropolis/ metro2.jpg&w=445&h=292&ei=mygXUPq2BcvPqAHm2YGoAw&zoom=1&iact=hc&vpx=858&vpy=150&dur=156&hovh=182&hovw=277&tx=140&ty=75&sig=116098570927455928649&page=1&tbnh=108&tbnw=165&start=0&ndsp=40&ved=1t:429,r:4,s:0,i:87

6. Nevada ghost towns‐Tuscarora. http://www.ghoscowns.com/states/nv/tuscarora.html

7. Tuscarora in Elko County. http://nvghoscowns.topcites.com/pastpro/tuscaror.htm

8. Nell Murbarger,“Printer of Old Tuscarora,”in The Desert Magazine, January 1950, pp.27‐52. http://www.dezertmagazine.com/mine/1950DM01/index.html

9. Nevada Ghost Towns – Charleston. http://www.ghoscowns.com/states/nv/charleston.html

10.Nevada Ghost Towns – Madris and Charleston. http://www.nevadadventures.com/ghost%20towns/elkocounty/charleston/charleston.html

11.Nevada – Jarbidge. http://www.nevadaweb.com/cnt/cc/jrbg.html

12.Nevada Ghost Towns – Jarbidge. http://www.ghoscowns.com/states/nv/jarbidge.html

13.Jarbidge, Nevada. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jarbidge,_Nevada

14.Nevada Adventures – Jarbidge. http://www.nevadadventures.com/communi<es/elko/jarbidge/jarbidgemain.html

15.Nevada ghost towns – Rowland. http://www.ghoscowns.com/states/nv/rowland.htm

16.Nevada Ghost Towns – Rowland. http://nvghoscowns.topcites.com/elko/elkolst2.htm

17.Shawn Hall, “Rowland,” in Old Heart of Nevada,1998, pp.133‐136. https://www.google.com/search?q=history+of+rowland+nevada&ie=uf‐8&oe=uf‐8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en‐US:official&client=firefox‐a

18.Idaho Ghost Towns – Three Creek. http://www.ghoscowns.com/states/id/threecreek.html

19.Forum for history of ghost towns and historical sites – Three Creek Store and Post Office. http://forums.ghoscowns.com/showthread.php?18248‐Three‐Creek‐Idaho‐where‐I‐grew‐up&highlight=creek+store

20.Owyhee County, Idaho Gen Web Project – Three Creek. http://www.owyhee.idgenweb.org/hstry‐place‐threecrk.html

21.The Wild Bunch in Winnemucca. http://nsla.nevadaculture.org/index.phpop<on=com_content&task=view&id=667&Itemid=95